Ghana: investing in water to boost prosperity

The dilapidated water supply in Ghana’s Volta Delta is thwarting the economy of the region. A major, multi-million dollar water infrastructure development project will help businesses grow and improve the lives of thousands of people. Find out how and why Deutsche Bank is helping to finance it.

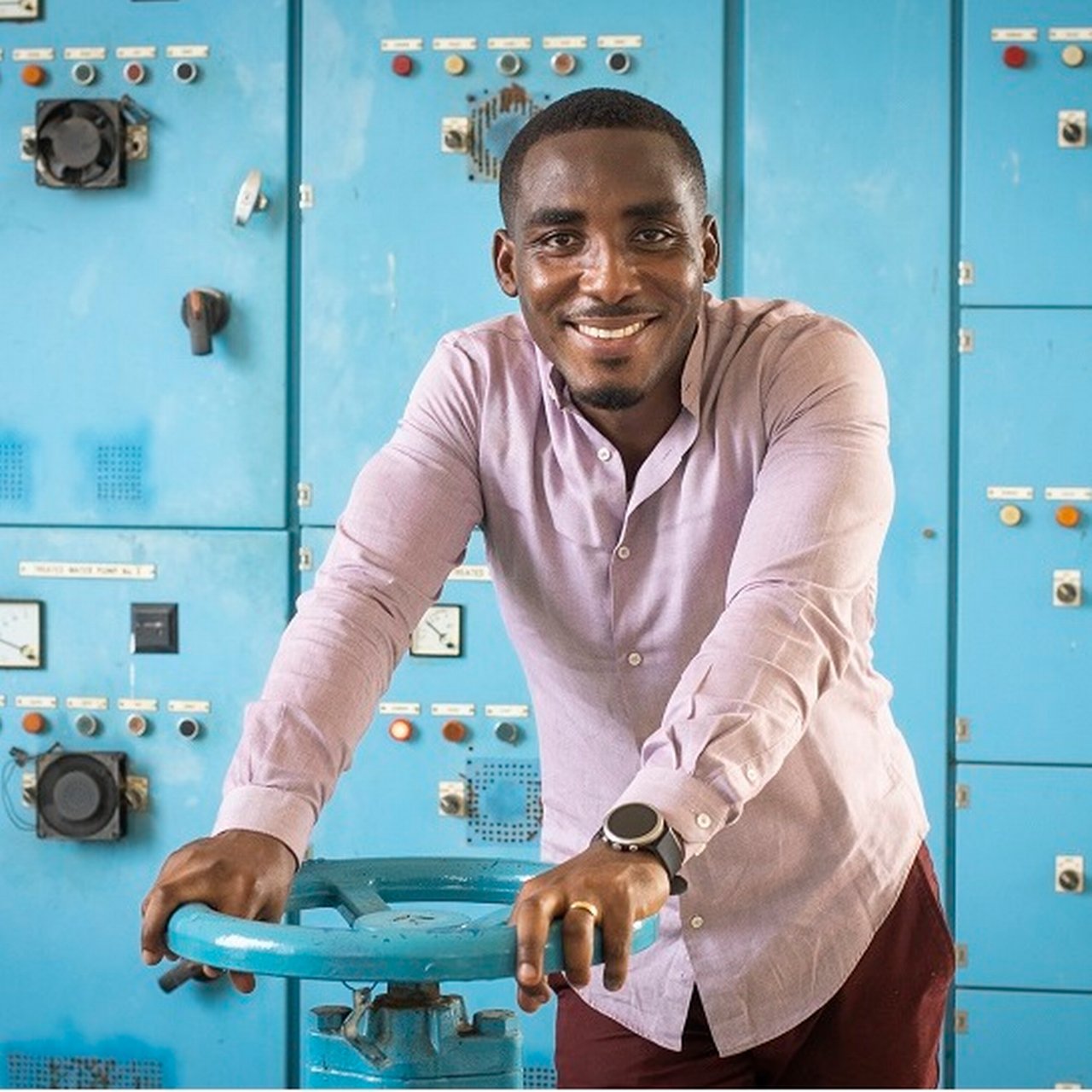

Between January and April, it's particularly tough. Philip Kojo Dawu's small farm on the outskirts of the town of Keta in southern Ghana suffers from drought. Located on the narrow headland between the lagoon and the ocean, the town not only lacks rain, but the lack of water is increasing the salinity in the groundwater as well.

Between January and April, it's particularly tough. Philip Kojo Dawu's small farm on the outskirts of the town of Keta in southern Ghana suffers from drought. Located on the narrow headland between the lagoon and the ocean, the town not only lacks rain, but the lack of water is increasing the salinity in the groundwater as well.

Dawu grows bell pepper plants and irrigates his field with water he obtains from a so-called "borehole" – a well he drilled himself. "Here on our farm the water is too salty, we can’t take it to grow our crops. We have to fetch it from a place behind the farm. The salt spoils the soil, and what you grow in it doesn't grow properly. So you sometimes lose parts of the harvest like that, and with it your invested money – and then you even need to buy new crop and start all over again."

Clean water is hard to come by

Farmers, shopkeepers, fishermen, established entrepreneurs or start-ups: they all know that having a reliable water supply is the prime factor for economic prosperity in the Volta Delta. Located 160 kilometres east of Ghana's capital Accra and at the delta of a river, the region is actually very fertile – but not without water. Few families have the luxury of running water at home.  For those that do, the water only trickles out of the tap because the water infrastructure in the Volta Delta is old and dilapidated.

For those that do, the water only trickles out of the tap because the water infrastructure in the Volta Delta is old and dilapidated.

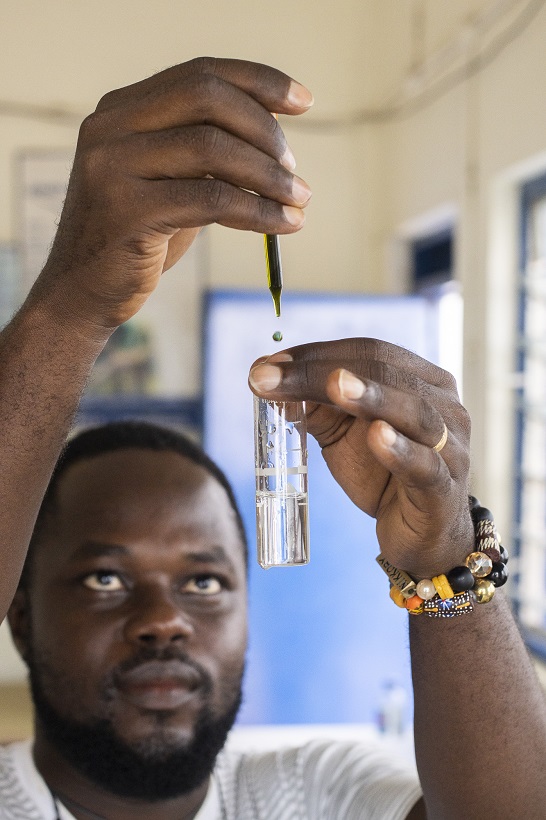

Many people are dependent on public water points. But even these are unreliable, forcing people to resort to well water – water that is barely drinkable. That’s why Millicent Nyaho sells what she calls “pure water” in her shop. It comes in sachets. "A lot of people from every class buy it. They take it for drinking and cooking because the water from the wells is not clean," says Nyaho.

Water only once a week

Numerous communities in the region have no water supply at all. Some places are supplied with mobile water tanks from the state-owned Ghana Water Company, but this often only comes once a week. Many people travel long distances to buy water directly from the water company, fill their canisters with it and transport it home.

But this is far from healthy, knows Somuah Tenkorang, an engineer at the headquarters of the Ghana Water Company in Accra: "Even the water from the tanks can sometimes be of poor quality, because if you do not handle it well from the trucks into the homes, it can get contaminated and cause a lot of health problems." Both the long distances and the unavoidable use of water from wells or boreholes increase the likelihood of disease, prevent proper irrigation and result in the entire south-eastern part of the country stagnating.

No water, no growth

An entire region stymied in economic terms. Yet Ghana is on a promising path: compared to neighbouring countries, the country has achieved a higher level of prosperity and, according to the World Bank, has an annual GDP growth rate of over 6 percent. The population is growing by only 2.2 percent a year, giving Ghana the lowest population growth of any country in southern West Africa. Agriculture contributes about one-fifth of the gross national product and is thus an important economic factor.

The population is growing by only 2.2 percent a year, giving Ghana the lowest population growth of any country in southern West Africa. Agriculture contributes about one-fifth of the gross national product and is thus an important economic factor.

In recent years, the country has made great strides toward democracy under a multiparty system, thanks in part to its independent judiciary. Ghana consistently ranks among Africa's top three countries in terms of freedom of expression and freedom of the press. Factors such as these endow Ghana with solid social capital. In the southern Volta region, however, much of its economic potential lies fallow.

Lack of water is blocking investment

Godwin Edudzi Effah is Keta’s municipal chief executive and sees the extent to which poor infrastructure is holding back the region’s development every day when he looks out of the window of his office: "The population is growing thanks to the new nursing school and the large port project. But many people in this area don't have water at home," says Effah. "Their quality of life would greatly improve with access to clean water. It would also attract new businesses and companies."

In fact, poor water supply has repeatedly prevented new businesses from locating here. Currently, a project by Asian investors is on hold because of this. The local construction industry and fishermen are also clamouring for access to an improved water infrastructure. "A better water supply would raise the standard of living in the entire region," adds Effah. "And it would discourage young people from moving to Accra."

In fact, poor water supply has repeatedly prevented new businesses from locating here. Currently, a project by Asian investors is on hold because of this. The local construction industry and fishermen are also clamouring for access to an improved water infrastructure. "A better water supply would raise the standard of living in the entire region," adds Effah. "And it would discourage young people from moving to Accra."

Water for 400,000 people

To prevent the exodus of young talent to the capital, boost economic growth in the region, secure existing jobs and create new ones, the Ghanaian government is investing heavily in the region's water supply as part of a nationwide infrastructure offensive. The “Keta Water Supply Rehabilitation and Expansion Project,” commissioned by the Ghana Water Company, includes the rehabilitation of the existing water treatment plant in Agordome on the bank of the Volta river inland, and the construction of an additional plant in the city with a joint capacity of more than 42,000 cubic meters per day.

Once completed, both plants, together with the newly constructed pipeline, a booster station and additional reservoirs, will be able to meet the water needs of over 400,000 residents on the Keta Peninsula.

Deutsche Bank finances part of the multi-million project

The 85 million euro financing guaranteed by the Italian export credit agency SACE will enable the construction of this infrastructure project. Deutsche Bank was mandated as lead arranger and facility agent in the transaction, and Germany's AKA Ausfuhrkredit-Gesellschaft Bank participated with 50 percent of the financing.

"The main benefit is improved livelihood and lifestyle", says engineer Immanuel. "People will no longer have to share water with livestock. They will have more income because they won't have to spend as much money on health care, school children won't have to get up at the crack of dawn to fetch water for their families before going to school. Small industries will have more confidence to invest in this region. So people will soon earn more and living standards will rise.”

The main benefit is improved livelihood and lifestyle. Small industries will have more confidence to invest in this region. So people will soon earn more and living standards will rise.

Providing an impetus for growth in a region that is full of potential: that is also the motivation for Deutsche Bank to be part of this project. "Deutsche Bank has a longstanding presence in Africa and we are proud to be a leading export finance partner for Ghana," says Werner Schmidt, Global Head of Structured Trade Export Finance at Deutsche Bank. "We remain committed to supporting infrastructure projects that have a positive impact on communities and which contribute to long-term economic growth."

The bank uses its expertise in structuring and organising financing to help countries like Ghana access global capital markets. Since 2011, Deutsche Bank has provided more than 20 billion euros to support infrastructure development in Ghana.

Stimulating the economy far beyond Ghana

Without a constant water supply, the planned new port facility with a fish factory and loading terminals would be unthinkable. With the port, a logistics center of strategic importance is being created in Keta, which will stimulate the economy in the region – far beyond Ghana. The country’s third seaport will also serve as a gateway to the sea for neighbouring landlocked countries such as Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali.

But a constant supply of clean water will also be a boost for small businesses in the region: "I will happily use water from the tap, because the water from the well is hard and often doesn't mix well with the products we use," says Agnes Gudolo, who runs a hair salon in Keta. She is counting on satisfied customers and increasing demand for her service when a modernised infrastructure reliably supplies clean, soft water.

Godwin Sotama hopes the same – albeit on a much larger scale. The CEO of Selasie Beverages, a medium-sized drinks manufacturer and bottler, has mango juice and drinking water bottled here, on the outskirts of Lolito, about ten kilometers from the banks of the Volta River and the plant in Agordome. "The water is very polluted when it comes out of the pipes. So we have to filter it again. And then it also has to go through reverse osmosis before we can use it," he says.

And because sometimes not a drop comes out of the pipe for days, he says he has to organise a truck every now and then to fetch the water from Agordome. His prediction: "We would benefit a lot if the new project would deliver water with more reliability. Our business could expand because we would have constant production."

Full throttle for better peppers

Farmer Philip Kojo Dawu of Keta is also pinning his hopes on the water infrastructure expansion, which he hopes will make his production less dependent on the vagaries of the weather and climatic change: "When we get the water from the new pipeline, I will be very happy because our production will be persistent throughout the year.”

Photographs by Espen Eichhöfer, OSTKREUZ Agentur der Fotografen

Water in the southern Volta region

- In the southern Volta region, water supply largely consists of pumping from local boreholes and is unable to meet the increasing demands of a growing population.

- The state-owned Ghana Water Company Limited has commissioned the “Keta Water Supply Rehabilitation and Expansion Project” to improve water and sanitation services in the region.

- The project, with a contract value of 85 million euros, includes the rehabilitation of the existing water treatment plant in Agordome and the construction of another treatment plant in the city.

- Once completed, the water infrastructure will be able to meet the current and future water needs of over 400,000 inhabitants in the municipalities of Keta, Anloga and Tongu by 2030.

Recommended content

“We need to create a greener economy” “We need to create a greener economy”

Why behavioural scientist Jane Goodall sees a connection between climate crisis and the pandemic, about biodiversity as our tapestry of life, the possible contribution of governments and global institutions like Deutsche Bank to a new and respectful relationship with the natural world. And what advice her mother gave her at the age of 10.

“We need to create a greener economy” Why we need healthy ecosystemsThe power of blue The power of blue

Will greater investment in water resources make for a more sustainable future?

The power of blue About banks and waterWhy a healthy ocean costs 175 billion US dollars a year (and why that’s a bargain) Why a healthy ocean costs 175 billion US dollars a year

The United Nations adopted the protection and sustainable use of the oceans as a major sustainable development goal. Yet the oceans are not in good shape.

Why a healthy ocean costs 175 billion US dollars a year (and why that’s a bargain) Dive-in!